Revision to GAFTA sampling rules

Since I started in this business in the 1990s, much of my work has been with grains and animal feedstuffs. Huge quantities of grain and feeds are traded by sea, and it is no exaggeration to say that this trade is necessary to feed the world. It is a widely quoted statistic that 80% of the world trade in grain and animal feeds is by means of GAFTA contracts.

GAFTA is an acronym for the Grain and Feed Trade Association. I’m pleased to be able to say that Sheard Scientific is a member of GAFTA.

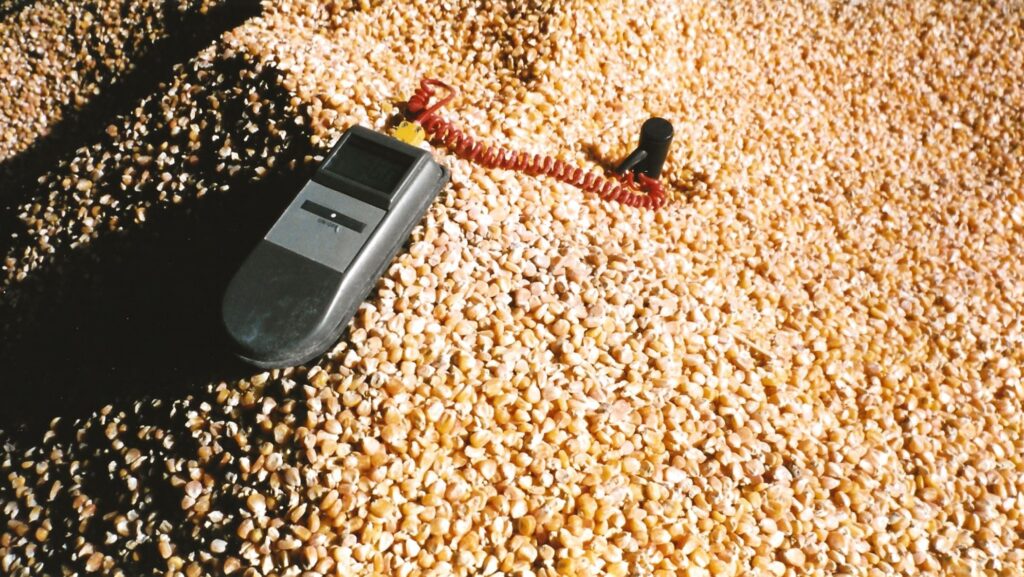

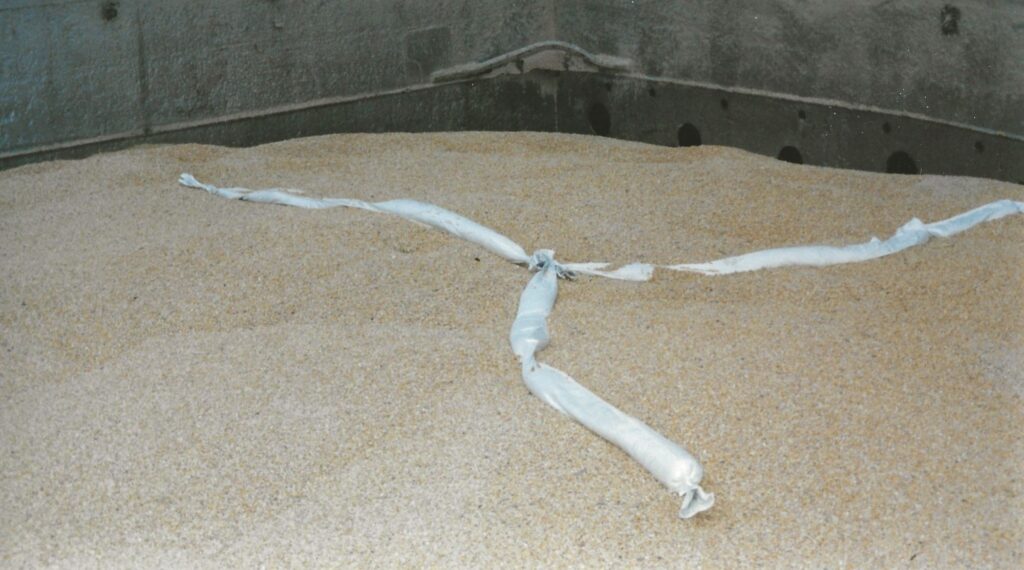

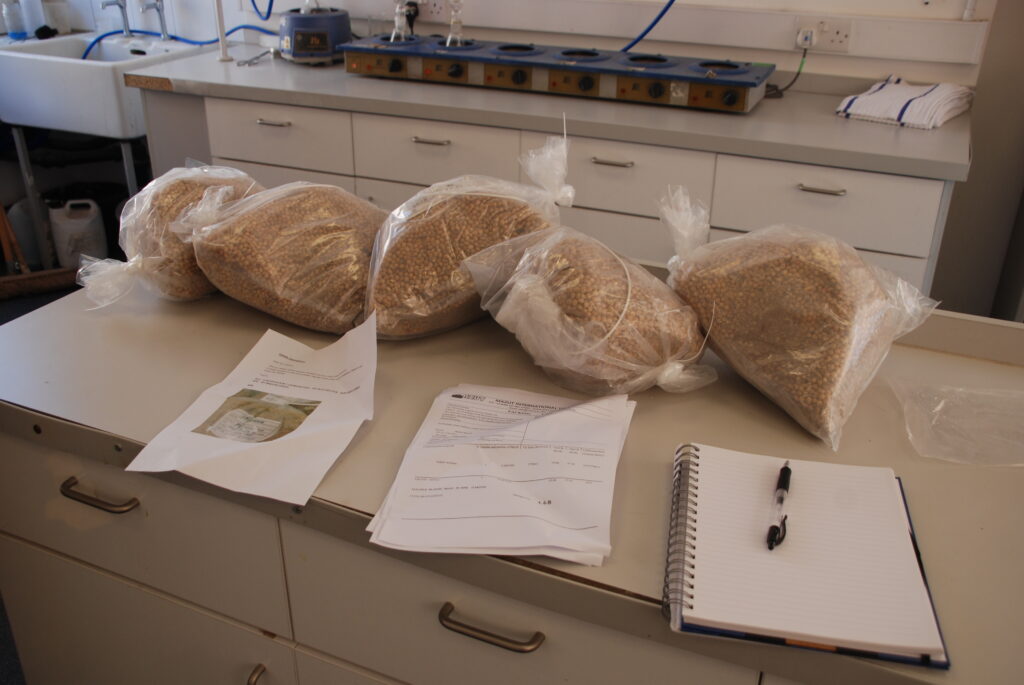

Trade based on GAFTA contracts usually adopts the concept that the definitive and “final” check on the quality of the goods being traded occurs at the time of loading. This enables a degree of certainty to those participating in the trade, but the concept does require reliable sampling and analysis. That sampling is required to be carried out according to GAFTA 124 sampling rules.

I may write in more detail about sampling as a general topic in a later post (time allowing!), but suffice it to say here that representative samples by definition are to represent the average properties of the parcel of cargo being sampled. Since those samples have to be much smaller in size than the cargo they are drawn from, they have to be drawn in a manner which gives equal statistical chance for any given particle in the cargo being sampled to be in the working/drawn sample.

The purpose of GAFTA 124 is to set a standard for how that is to be carried out, how the integrity of the samples should be preserved, and what should be done with them. Whilst the official scope of GAFTA 124 is in reference to the GAFTA sales and purchase contracts, to ensure quality parameters are properly and reliably assessed when a cargo is traded, it is in my experience so commonplace as to be universal that they are used as a benchmark “gold standard” for sampling of cargoes where there is a dispute – in circumstances where there has been transit damage, for instance. The GAFTA sampling rules don’t necessarily suit all such circumstances, but they are always where surveyors and experts start when considering how to sample average parameters of bulk grain or feeds.

Bearing that in mind, a change to the GAFTA 124 rules is potentially big news, and so I read with interest when I received notification of the changes. There have been substantial changes to the GAFTA 124 rules over the years I have been working in this industry – when I first started, in all cases sublots were 500MT in size – meaning dozens of sublots for a moderate sized vessel. That has long-since been changed so that the selection of sublot sizing scales with the overall consignment quantity.

One change being introduced in the new version of the rules is that there is greater clarity regarding the numbers of individual bags from which samples must be taken when bagged goods are being sampled.

Paragraph 9.1.8 now contains the following text, seemingly to ensure that all are made aware of the status of “certificate final” provisions and that sets of samples reserved for arbitration are not to be used to overturn compliant load port certification.

Arbitration samples drawn for goods traded on contracts stating ‘Quality (Certificate) Final’ at loading or at discharge cannot be used to challenge the quality specifications which are included in the ‘Quality (Certificate) Final’ certificate, unless otherwise determined by arbitrators or Board of Appeal.

But to my eyes, the biggest change is in the selection of laboratories. Again, back when I started this work, in the case of any disputes or disagreements, specific laboratories were to be used as “referee” laboratories. In recent years there have been four designated as referee laboratories and their identities were written into GAFTA 124. The four reference laboratories were undeniably “household names” to all in the grain trade, and will no doubt continue to be used as reliable grain testing facilities. However, it is now the case that any GAFTA-approved laboratory can serve this purpose as all approved labs are considered equivalent.

What makes a cargo scientist?

It has been a while since I wrote something for this blog and website. In this post I will talk about my work in general terms.

You may have seen the phrase “cargo scientist” being used to describe people who work in my line of business, but where does that phrase come from and what does it mean? “Cargo scientist” is a phrase coined in recent years, possibly because there hasn’t really been a better way of describing the various aspects of the role.

In the olden days, much of the work carried out by my predecessors was in relation to grain and animal feeds – crops. There was a tendency for those who provided expert evidence in this field to be described by the legal profession who instructed them as “agronomists”. The dictionary definition of an agronomist is “an expert in the science of soil management and crop production”. That then is a fairly clear expression of something I don’t ever do! All of my work involving grains and animal feedstuffs relates to the post-harvest handling and storage of those agricultural materials. Most of it involves carriage at sea, which has some similarities but many differences to land-based storage facilities such as silos. That’s just the agricultural products.

I also provide advice on other types of commodity; coal and wood pellets, ores and minerals, fertilisers, chilled and frozen produce, edible oils and fats, chemicals, and so on; most things that can be put on a ship and carried whether in bulk or packaged into bags or drums. Then there are the more abstract topics which result in problems and disputes – cargo liquefaction, ventilation as its own topic, fumigation, sampling and analysis.

To be a good cargo scientist you need a number of things.

Firstly, you need a strong grounding in the natural sciences. Mostly the knowedge and concepts required are “A” level or early years University level in complexity, but any one case may involve knowledge of physics, chemistry and biology, applied to the various aspects in a case. Thus, as an example, deterioration of soya beans may involve microbiological growth. That requires an understanding of the lifecycle and conditions for growth of yeasts and moulds. Once parts of the stow heat, there may be a temperature gradient or condensation, considerations about which require an understanding of physics. Published data on temperature and moisture for soya beans may need to be converted from one set of units or basis to another (some maths required!). Evaluating the loss to the oil in the beans requires an understanding of the chemistry of oil hydrolysis. And so on.

I’m fortunate that my undergraduate degree course involved studying (initially) three sciences rather than specialising in one subject from the first year. This gives me a broad grounding in the fundamentals of science. I have since starting this work studied for further qualifications, and am still doing so.

Secondly, you need a wide knowledge of the types of cargo carried at sea and an understanding of what the relevant issues or problems with each are likely to be. This knowledge and experience tends to increase with time spent in the industry.

Thirdly, you need to have an analytical mind and the ability to approach unknown problems with a flexible but systematic approach. Even though I have been in this business for most of my working life, and have over 25 years’ experience in cargoes, there are still some commodities or specific tests/parameters that I experience for the first time. Being a cargo scientist means that I know how to approach unknowns and establish a way of tackling the problem and gaining the necessary background knowledge from published data or other sources.

All of these aspects of the work have one thing in common – the use of a scientific approach to explain, diagnose or predict the behaviour of cargoes on ships or in storage. Occasionally advanced or complex science/mathematics is required, but in most instances that isn’t the case. That is one reason why most cargo scientists have Ph.D degrees. It isn’t because the topic studied for the doctorate is necessarily of value to the cargo science job – it rarely is. Studying for a Ph.D involves learning how to carry out research into unfamiliar topics, and how to access and reference scientific literature – essential skills for working as a cargo scientist.

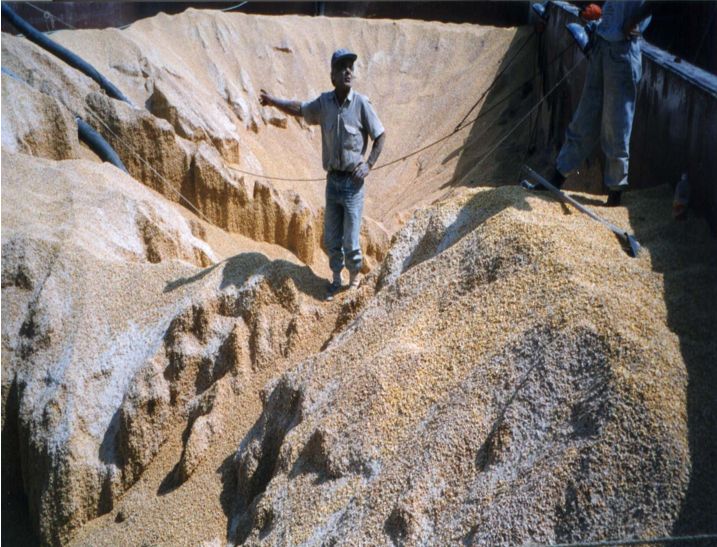

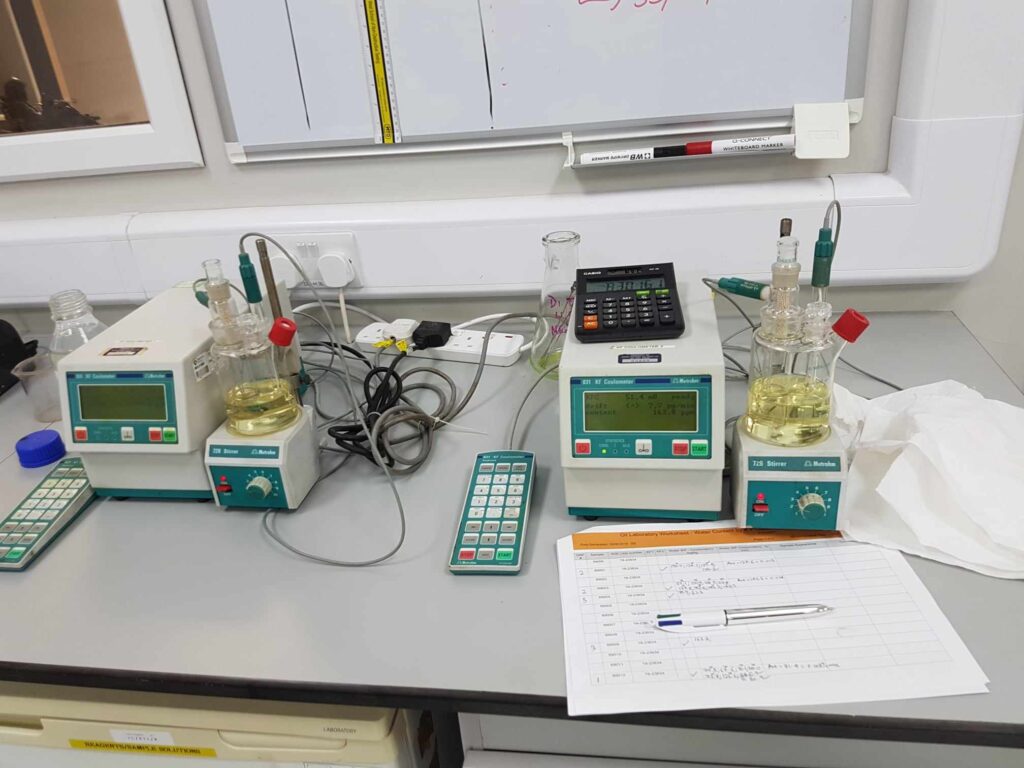

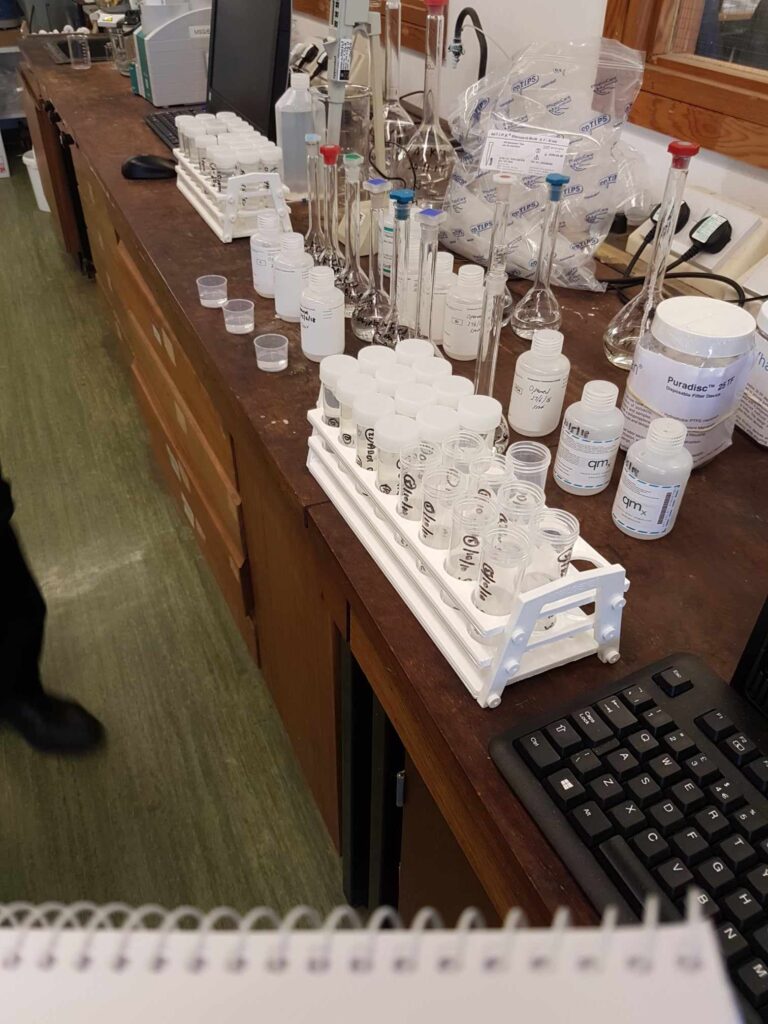

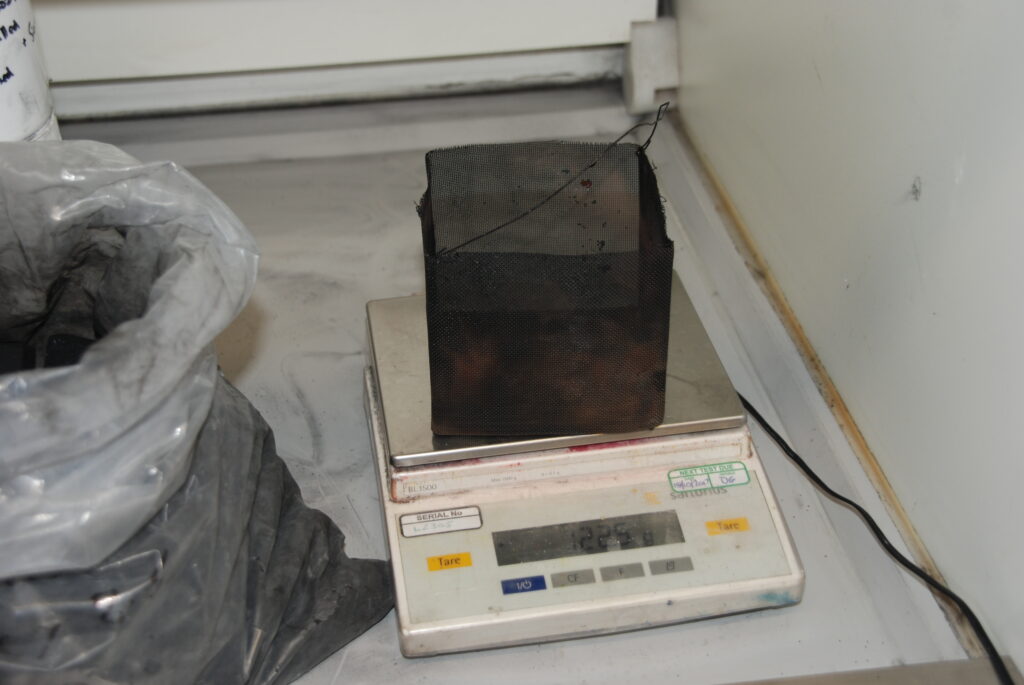

So what do I actually do? Over the years I have worked in this industry, I have dealt with many types of cargo problem in the field as set out above. I’ve climbed ladders, shovelled mouldy grain, taken a very large number of photographs of cargoes, measured temperature on hundreds if not thousands of occasions (why temperature? – that will be the subject of a later post), watched grain flow or not flow during discharge, seen fertiliser on ships and under test in laboratories, sampled cargoes on many occasions, dealt with fires first-hand, seen liquefied bulk cargoes, tested bulk cargoes for transportable moisture limit, witnessed analysis of many different kinds, and have had numerous heated discussions with cargo receivers and surveyors!

The other part of the role of a cargo scientist is reviewing documentary evidence about a case, considering the technical aspects of it, writing expert reports, reviewing opponent expert reports and providing commentary on them, holding expert meetings, and ultimately, providing an expert witness service in Court or Arbitration proceedings (on paper or live in hearings). I have worked on a very large quantity of all aspects of these kinds of cases.

Times have changed since I first starting work in this field. We had one mobile phone for the company, and that didn’t work in most overseas countries. Many times I flew somewhere to discover on arrival that the problem wasn’t quite what the client thought it was. Now, in contrast, there are many excellent surveyors in ports worldwide (hello to any of them reading this!); they all have mobile phones with good cameras. Rather than having to wait weeks or months for a report, clients receive regular updates with photographs or even video footage. From the UK I am able to direct matters remotely, holding video calls when I need to see things myself. The sequence of lockdowns and travel restrictions during the height of the COVID pandemic showed the world that it was possible to investigate and resolve many matters without being able to fly experts around the world. For many cases now, the huge costs of someone travelling out to a vessel are simply not required.

I knew when setting up Sheard Scientific as a new entity that there was plenty of room in the market for a new organisation offering cargo scientist expertise. That has been the case for as long as I have worked in this field – many years ago the field was dominated by Dr RF Milton & Partners, later Jarrett Kirman & Willems, but there were a substantial number of individuals specialising in one type of cargo or another to service the clients’ requirements for independent organisations to instruct. There are fewer such independent indviduals operating today – the expertise has become concentrated in a very small number of firms worldwide, some of which are owned by larger entities.

There is, in my view, no substitute for genuinely independent scientifically-based expertise coupled with vast experience in the field and in providing expert evidence. That is what we offer.