A trip to Whitby – Dracula, Captain Cook and the Scoresbys

A younger member of the Sheard household is studying literature (and fancies herself a bit of a Goth), so we had a trip to Whitby in North Yorkshire to see what we could discover about Bram Stoker’s inspiration for Dracula.

Vampires aside, Whitby of course has a proud maritime history. Captain James Cook was born and lived nearby and explored huge previously uncharted parts of the world.

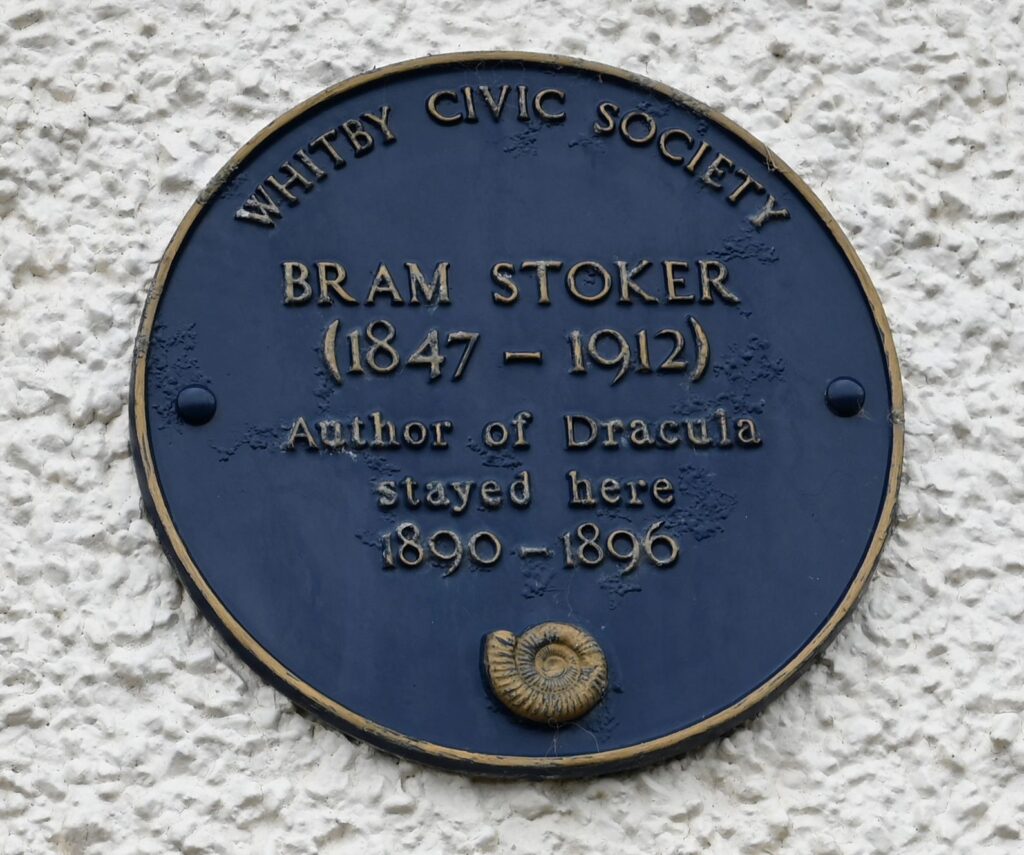

The focus of our trip however was Dracula, written by Bram Stoker, a frequent visitor to Whitby.

In the story, Dracula arrived at Whitby by sea and some of the novel is set in the graveyard of St Mary’s Church, near the Abbey.

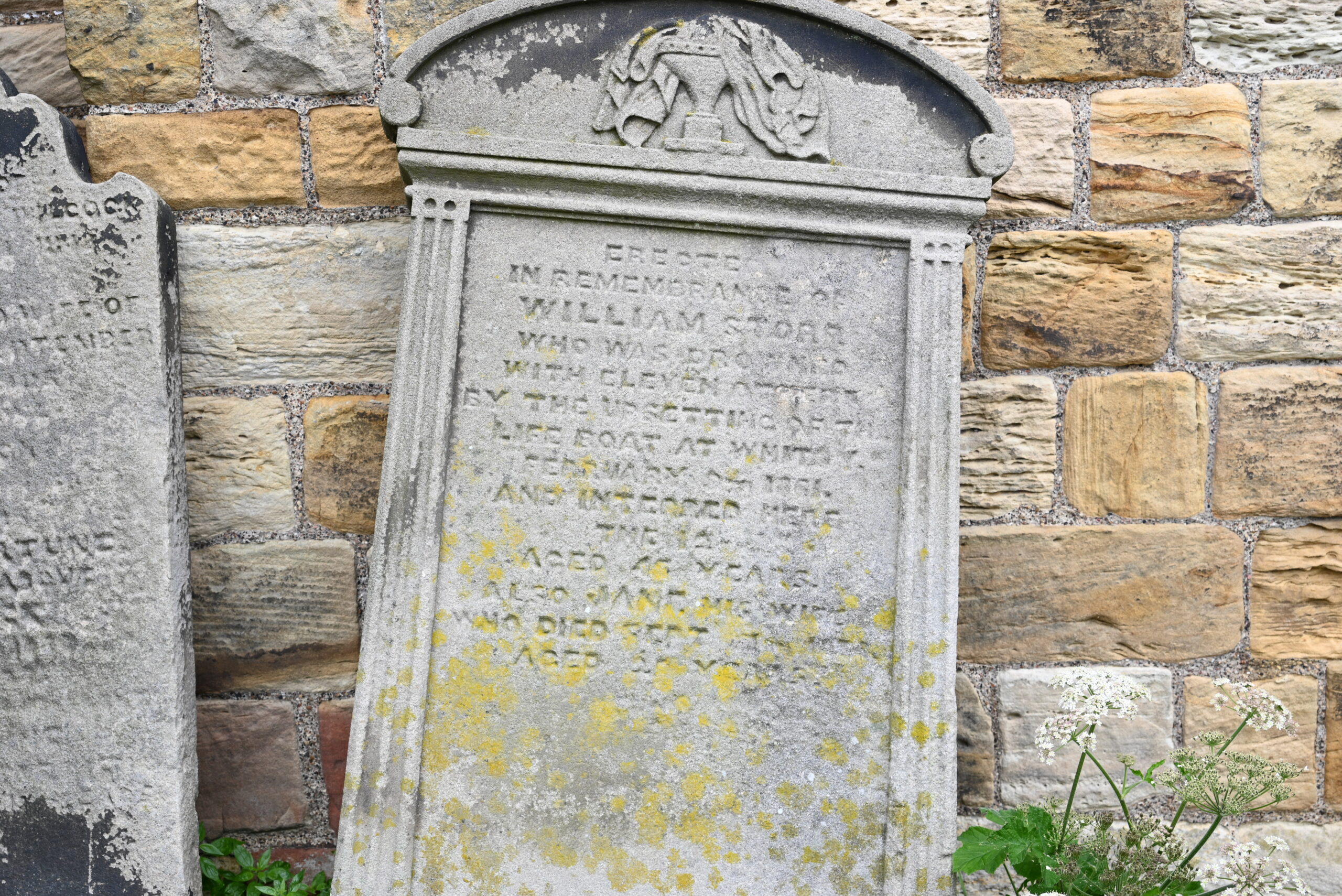

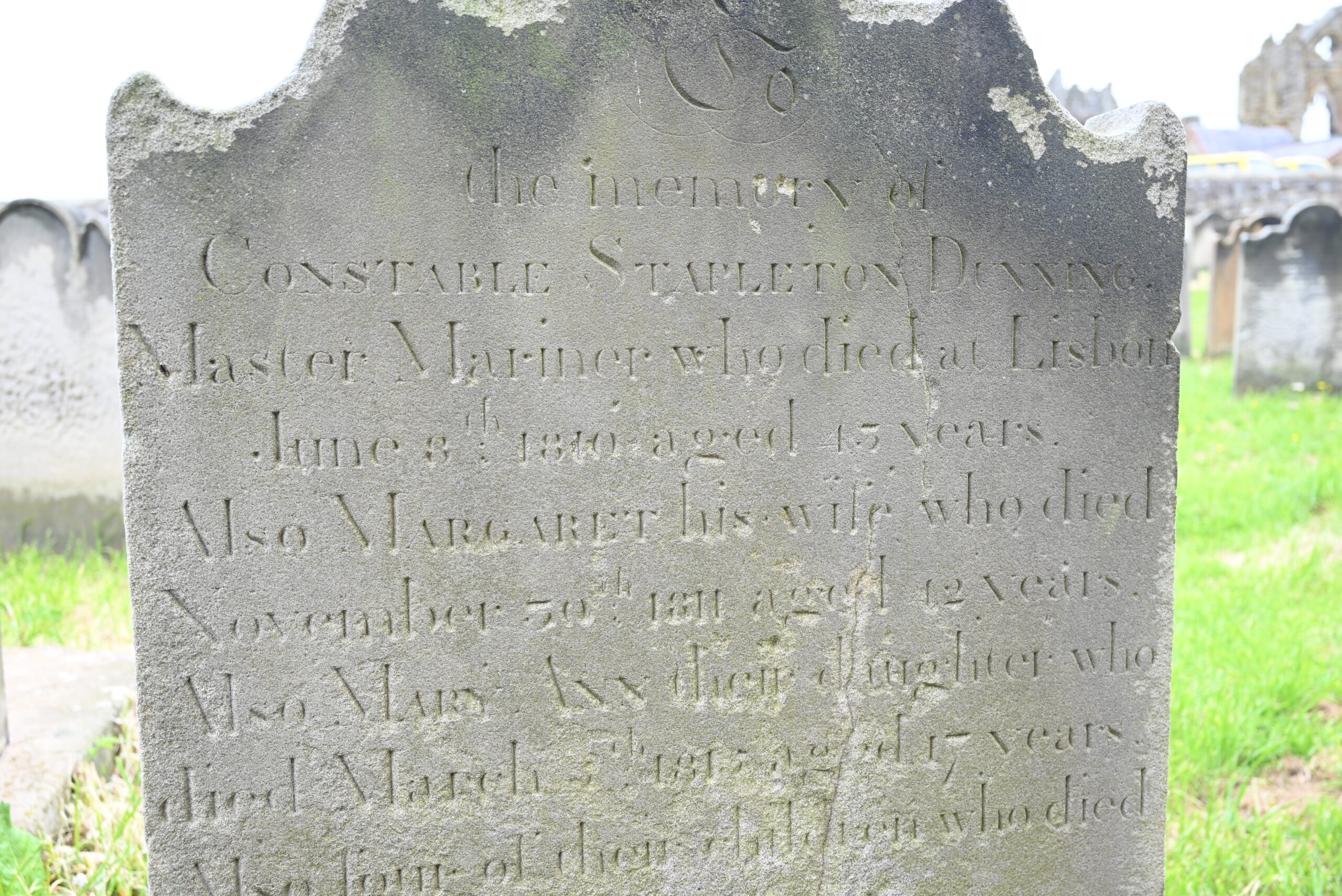

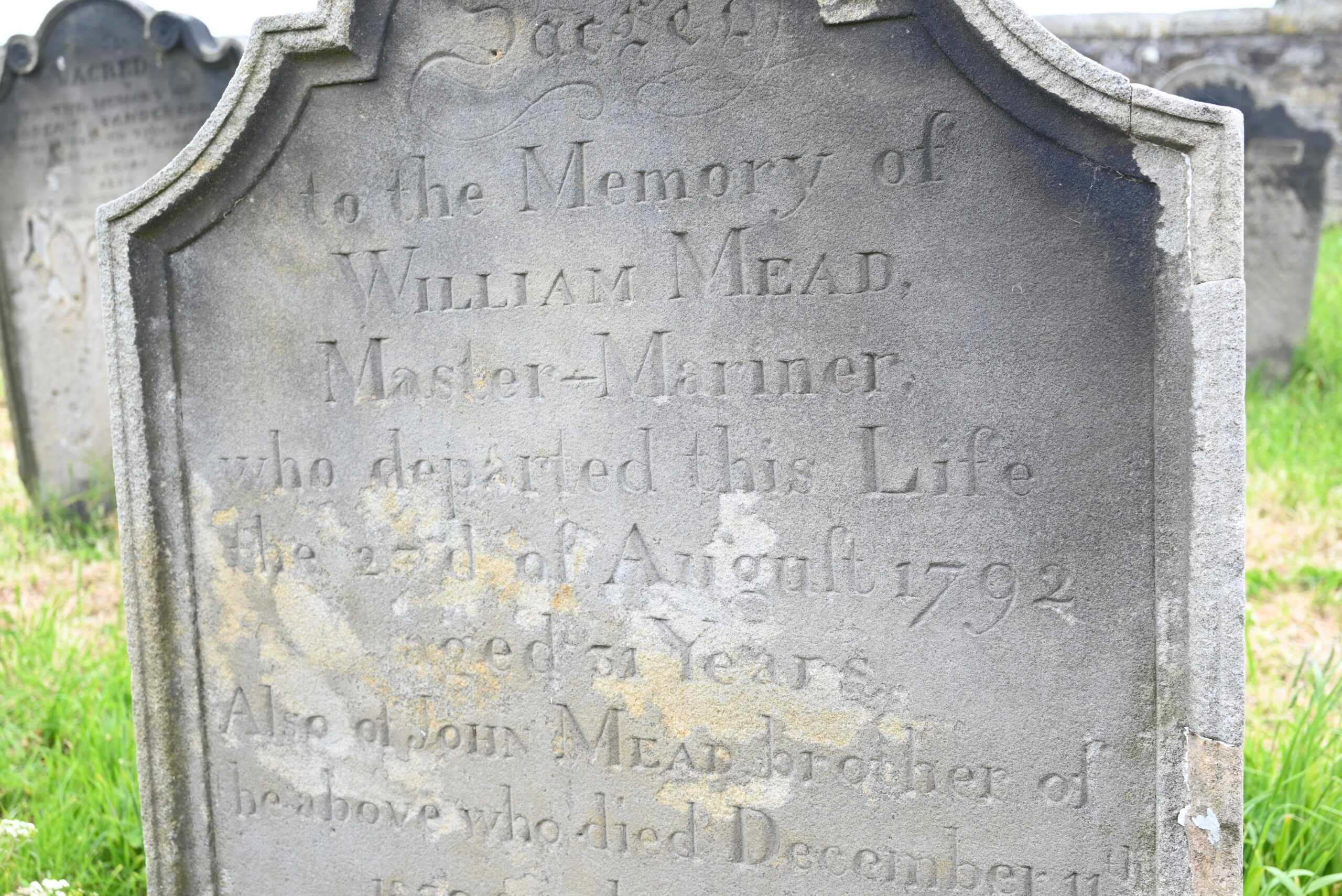

Wandering around the churchyard, we didn’t find any vampires but we did find numerous Master Mariners. Many of the graves are actually memorial stones to those lost at sea.

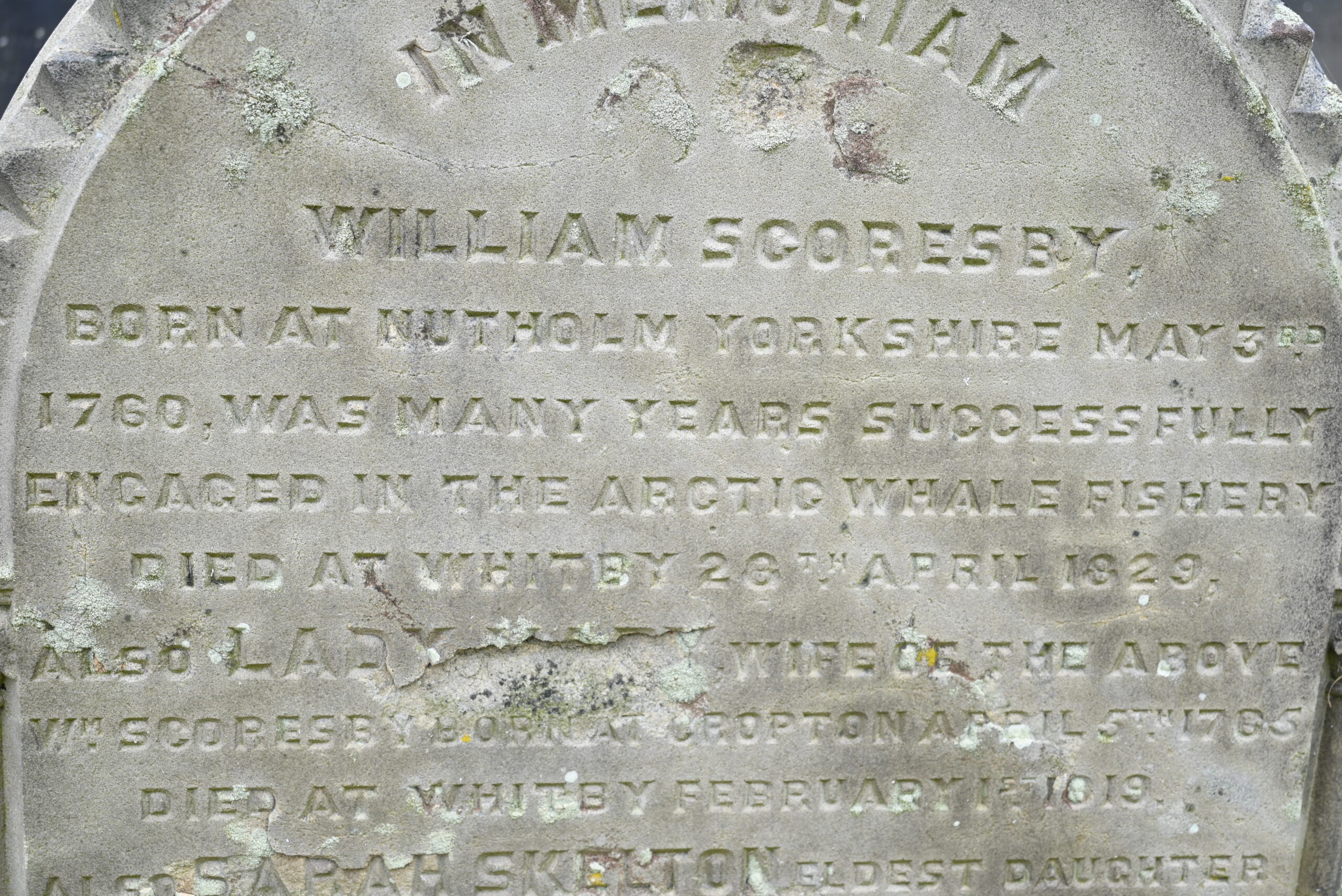

Nearby in the churchyard, however, we located something of significant interest historically and scientifically – the grave of William Scoresby.

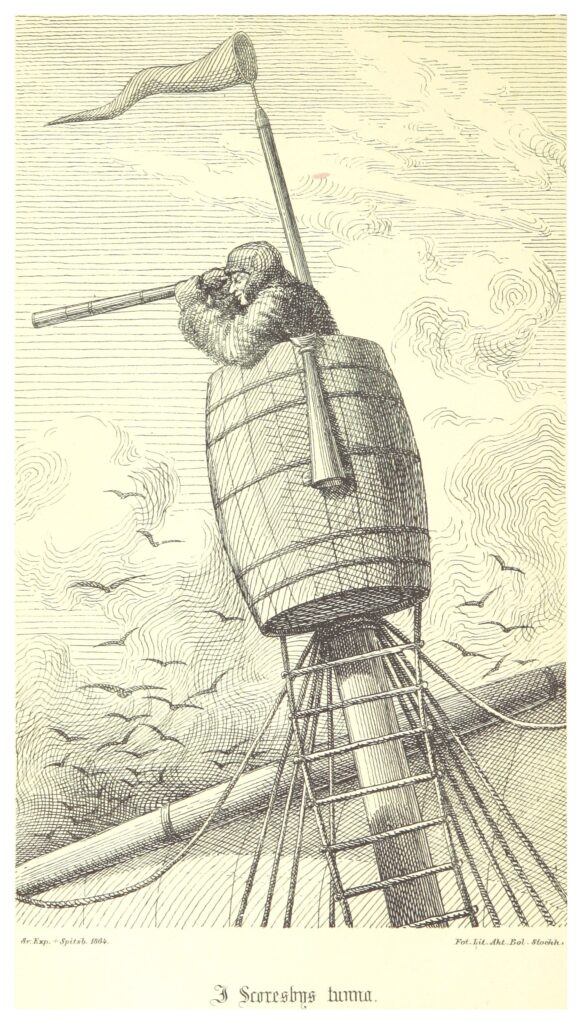

William Scoresby made his fortune in Arctic whaling. He is often credited as the inventor of the ship’s crows nest. Elevated lookouts on ships may have existed prior to Mr Scoresby, but he apparently did originate the barrel crows nest.

In the church itself is a chair known as the Scoresby Chair, which was carved from the remains of the vessel ROYAL CHARTER, on which William’s son, Rev William Scoresby carried out scientific experiments.

Rev William Scoresby spent many years working on the problem of compass deviation on ships incorporating iron as part of their structure. His views brought him into conflict with the Astronomer Royal, Sir George Biddell Airy with such vehemence that the issue became known as the Airy-Scoresby Controversy.

The problem is that iron in a ship’s structure can become magnetised and interfere with the operation of a navigation compass. Numerous ships were lost as a consequence.

Airy proposed a solution in which the ship would be “swung” through the points of the compass and the behaviour of the navigation compass checked at each orientation. Iron masses were then added in the vicinity of the compass to neutralise empirically the effect of the iron ship structure on the compass readings.

Scoresby believed this approach was so wrong as to be dangerous, and said so during a speech he gave to the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Liverpool. He believed the magnetic effect of the iron in a ship’s structure could suddenly and unpredictably change as a consequence of the vibrations set up by her motion in a seaway.

To investigate this, Rev Scoresby sailed around the world via Australia on ROYAL CHARTER in 1856 and took a large number of compass readings during the voyage. He aimed to demonstrate his theory of shifting magnetic influence by means of these observations.

Rev Scoresby died in 1857, and ROYAL CHARTER sank in 1859. The outcome of the controversy was that Airy’s system of compensating massess was retained, but one of Scoresby’s innovations, locating a “pole compass” on a mast and away from the ship’s iron structure, was incorporated to improve maritime safety.

A small part of ROYAL CHARTER lives on in the Scoresby chair and if you visit Whitby, I suggest you take a look.

George Marriott and RMS CARMANIA

Today we’re thinking of our great-great uncle George Gascoigne Marriott who died in New York on 9 May 1918. George was a steward on Cunard’s Carmania, used at that time for troop transportation, and he was amongst the first wave of those who died during the so-called “Spanish” flu pandemic. George lived in sight of Liverpool, overlooking the Mersey.

The Carmania sailed from the city on 19 April 1918 and arrived in New York on 28 April. George was taken to St Vincent’s Hospital there on 2 May and died a week later. The Carmania was a Cunard steam turbine ocean liner. Her maiden voyage was from Liverpool to New York on 2 December 1905. She had berths for 2,650 passengers.

During World War 1 she was converted and became an AMC (Armed Merchant Cruiser) engaging with (and sinking) the SMS Cap Trafalgar (also a converted ocean liner) in 1914. An odd coincidence is that the Cap Trafalgar was disguised as the Carmania at the time!

From July 1916 Carmania was a troop ship, taking mainly Canadians home from war in Europe. George Marriott had been invalided out of the war in late 1917 and his trip to New York was the first, sadly last, job of his new civilian life.

Ironically, the recent pandemic meant we had to postpone our plans to visit George’s grave, but we hope one day to see his final resting place near other Cunard employees in Bay View Cemetery, New Jersey.

The depiction of the modern Liverpool skyline and Mersey ferries is by local artist Collette Collinge.