Fumigation of ships and cargoes has for many years been a source of problems to ship and cargo owners. Recently the UK MAIB issued a preliminary report into a serious incident on the vessel THORCO ANGELA, which happened in Liverpool in October 2021.

Insects are a fact of life. The Royal Entomological Society estimates that there are around 1.4 billion insects per each human alive on earth. The total mass of insects on earth is, they estimate, around 70 times the mass of all of the humans.

Hardly surprising then that agricultural cargoes (grains, oilseeds, animal feeds, etc) are at risk of becoming infested. Nobody wants that, and to avoid infestation cargoes must be treated every few months.

Insecticides can be sprayed onto a surface or cargo (“contact insecticides”) or can be applied as a gas (fumigants). Treating a large bulk with contact insecticide would require it to be sprayed (for instance) onto cargo on a conveyor. Using a fumigant is often more convenient as the gas can penetrate a large bulk.

The disadvantage is that it takes time for fumigant gas to diffuse throughout a large bulk. If in that time the gas starts to leak out, that’s bad for two reasons. Firstly, the fumigation may not be sufficiently effective (because the gas wasn’t present throughout the stow for long enough). Secondly, and much more important for safety reasons, if the gas isn’t staying the holds, it is going somewhere else. Fumigants are used because they kill insects. They can also kill humans or at the very least make them very ill indeed.

Most fumigation on ships these days uses a fumigant gas known as phosphine, chemically PH3. With very few exceptions this is deployed on ships by introducing solid preparations (tablets or pellets etc) into the hold. These solid materials contain aluminium or magnesium phosphide. These chemicals slowly react with atmospheric moisture in the hold and release the phosphine gas itself.

Phosphine is very dangerous. The recommended limit for spaces occupied by humans (NIOSH time weighted average) is 0.3ppm. But it isn’t just the toxicity. Phosphine is highly flammable in air, and in the real world, impurities commonly found in it can make it spontaneously explosive. Hatch covers can and have been blown into the air by phosphine explosions. The solid materials themselves can cause fires if they become wetted.

Fumigation on ships is, for these reasons, subject to IMO rules, recommendations and regulations. The IMO publication “Recommendations on the Safe Use of Pesticides on Ships Applicable to the Fumigation of Cargo Holds” has quite an unwieldy title, but contains guidance which should always be followed to ensure safety of life and vessel. This publication can be found as IMO Circular 1264, but it is also bundled as part of the IMSBC Code.

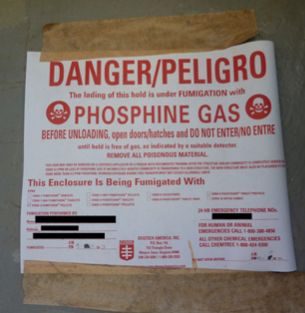

One part of the safety requirements is appropriate signage to indicate when fumigants are in use.

Standard shipboard gas meters are not designed to detect phosphine gas (although they have a sensor which may be referred to as a “toxic gas” sensor, they won’t help in keeping personnel safe). Specialist electronic meters exist, but they are quite expensive and no use for other tasks. Inexpensive glass detector tubes (made by Draeger or Gastec or similar) can be used but each tube can only be used once so you would get through a lot of such tubes in any particular practical deployment.

Lots of articles have set out the provisions to be found in IMO Circular 1264. I’m not going to do that here but I am going to discuss a point which came to the fore during the lockdowns applied as part of the worldwide response to the Coronavirus pandemic.

In the Circular, the following paragraph can be found.

Since fumigant gases are poisonous to humans and require special equipment and skills in application, they should be used by specialists and not by the ship’s crew.

IMO Circ. 1264. Para 3.1.2.2

Recommendations on the Safe Use of Pesticides on Ships Applicable to the Fumigation of Cargo Holds.

This provision is very clearly worded. The pandemic however caused all sorts of problems with many aspects of world trade. One particular trade customarily posted a trained fumigation operative to sail with a vessel as a supercargo. One of his duties was to monitor gas levels in the holds and add more solid phosphide preparation into the holds to “top up” the gas levels. I presume (or hope!) he would also carry out checks to establish where the gas was going, and to ensure that wasn’t going to cause problems.

With the Covid pandemic, this was no longer allowed. Getting personnel on and off ships became virtually impossible in many instances, and so a supercargo riding with the vessel was no longer viable.

The shipping world is full of “make do and adapt” attitudes – admirably so in many instances, but not here in my opinion. Initially, crews were supplied with the solid materials and asked to top up when required. No doubt this was done without incident on a number of occasions but it does violate the IMO Recommendations. As consultants we did not recommend carrying this out.

A second level of “work-around” was developed in which fumigation companies provided specific training to a designated crew member who thus became a “specialist”.

The organisations which were involved in this trade were relatively sophisticated and no doubt took this training seriously. However, once a precedent is created in which crew members are handling fumigants and fumigation materials, there becomes a possiblity that problems may arise if untrained crew members become involved.

Turning to the THORCO ANGELA incident (note, Sheard Scientific were not involved in investigating this), the MAIB report indicates that she loaded sweet potato in Rizhao, China. MAIB concluded that trained fumigators had not been allowed on the vessel and nor were any crew members supplied with sufficient training or equipment.

MAIB also conclude that the deployment of the solid phosphide material was done in such a way that the fumigant phosphine did not adequately “volatilise and disperse”. If the solid phosphide materials still contain substantial unreacted phosphide at the end of a voyage, they will still have the propensity to give off fresh phosphine gas.

One of the stevedores involved in discharging the cargo from THORCO ANGELA became unwell and was taken to hospital suffering with nausea, loss of balance, and nerve damage to his hand. MAIB note that Liverpool port had not been informed that the cargo was under fumigation. Thus the stevedores had no advance warning that there might be a problem.

This was undoubtedly a very serious incident, and it could easily have been very much worse. The takeaway lesson for those involved in carriage of cargo under fumigation should be to ensure that where alternative procedures are introduced (perhaps because there was no alternative), all effort should be made by all parties to make those alternative procedures as safe as the original ones. If ship’s crew are going to carry out the tasks which should be carried out by specially trained personnel, that can only take place if the crew members in question genuinely have received sufficient training.