A new Code – Part 2

So what’s new?

Starting with the Supplement, there is a new document entitled “Guidance for conducting the refined MHB (CR) test”. MHB materials are those with hazards which are not to be found in the IMDG Code as they are only considered hazardous when in bulk form. The application of MHB has changed in approach in recent years, and I will write about that separately.

The new document to be found in the Supplement relates to extending the scope of a UN Standard test (known as the C1 test) to apply to examining the corrosivity of bulk solids. The document notes that the C1 test in its standard published form does not give reliable results for bulk solids. The new guidance runs to several pages and is in effect a modification or adaptation to the C1 test enabling it to be conducted on bulk solids. This fortunately isn’t something most vessels will need to encounter.

Also in the Supplement is a new version of the document issued as circular 1395. This document contains “Lists of solid bulk cargoes for which a fixed gas fire-extinguishing system may be exempted or for which a fixed gas fire-extinguishing system is ineffective”. This document has been updated to include the materials to be found in the new Code schedules – see below. I note that this document relates to what are usually referred to as CO2 systems on ships. The CO2 system is frequently one of the first tools reached for by vessels undergoing a fire emergency. The first list in this document is made up of materials which are deemed very unlikely to support a fire. The second (for which a CO2 system is ineffective) is entirely made up of materials which are chemically inorganic nitrates. These are oxidising agents. As CO2 works by excluding oxygen and thus suppressing combustion, it is of no use for a cargo which contains its own oxidising agent.

Turning now to the main Code, a change which is really a matter of housekeeping from previous editions is the embedding of the concept of dynamic separation in the definitions and wording of parts of sections 1-13 of the Code (i.e. the bit before the appendices start). If you read my introduction to liquefaction, you may recall that dynamic separation as a phenomenon had been described in the new bauxite fines schedule. That schedule is of course to be found in Appendix 1 of the Code. No definition of dynamic separation existed in the sections of the Code discussing liquefaction, nor was there any wording to make it clear that Group A properties included both liquefaction and dynamic separation. Now there is.

The heading of Section 7, for instance is now “Cargoes which may liquefy or undergo dynamic separation“, whereas it was previously “Cargoes which may liquefy“. Similarly, the tests in Appendix 2 are now (all) tests for “materials which may liquefy or undergo dynamic separation.“

There is now a definition of the term “dynamic separation” itself, which is that

Dynamic separation means the phenomenon of forming a liquid slurry (water and fine solids) above the solid material, resulting in a free surface effect which may significantly affect the ship’s stability.

IMSBC Code definition of dynamic separation, 2022 Edition

This is the Code catching up with itself – the 2020 edition contained a schedule in an appendix which outlined a hazard which wasn’t defined in the Code itself. It is now very clear that dynamic separation and liquefaction are both to be taken as examples of Group A cargo behaviour. The procedure for preventing them is the same – Group A cargoes must be shipped at a moisture content below the determined Transportable Moisture Limit (TML).

Bearing that in mind, the distinction between liquefaction and dynamic separation only becomes significant when a cargo misbehaves. The emergency measures taken by a vessel may need to take into account whether the cargo is considered to be undergoing liquefaction or dynamic separation, but the normal routine handling and carriage does not.

Finally, I will turn to Appendix 1 – in this we find some new schedules and one commodity re-classified.

LEACH RESIDUE CONTAINING LEAD. This is a new schedule. It relates to solid residue produced during zinc extraction. Sulphuric acid is used to dissolve the zinc-bearing part of the ore or concentrate. What is left may contain lead (resulting in toxicity) and may be corrosive because of residual sulphuric acid. I note that this schedule is MHB TX and CR – the CR corrosive solid MHB hazard will require the new modified corrosivity test to be found in the Supplement. A Group A cargo on account of its particle sizing (granular), and a Group B cargo on account of the two MHB hazards.

CLAM SHELL. Another new schedule. Other than noting that it is Group C and relates only to whole clam shells, I have nothing to say!

SUPERPHOSPHATE (Triple, granular). This is a replacement schedule. In the previous edition of the Code, TSP (as it is usually known) was listed as a Group C cargo. The new schedule is a Group B schedule on account of it being a corrosive solid MHB. I note again that this requires the application of the new test to be found in the Supplement. TSP is the “ultimate” in a series of fertilisers obtaining fertilising phosphorous content (the P of NPK) manufactured from phosphate rock. Phosphate rock contains insoluble calcium phosphate, which is brought into solution by reacting with an acid. Sulphuric acid can be used which results in superphosphate. TSP has the highest amount of phosphorus in it, and it is made by reacting phosphoric acid with phosphate rock – the resulting material has phosphorus from both the phosphate rock and the phosphoric acid. Residual acidity results in the MHB CR designation.

… and finally, AMMONIUM NITRATE

There were four schedules for ammonium nitrate and material derived from it in the 2020 Code. They were

- Ammonium nitrate UN1942

- Ammonium nitrate based fertiliser UN2067

- Ammonium nitrate based fertiliser UN2071

- Ammonium nitrate based fertiliser (non-hazardous)

Of these, the “non hazardous” version was Group C and the first three were Group B cargoes. Note that ammonium nitrate in conjunction with combustible material such as fuel oil is highly explosive. One of the requirements to be considered non-hazardous was that the material passed the UN standard test known as the “trough test”. I wrote about this test and some of the problems arising from it earlier this year. I commented that the trough test did not fully reproduce the hazard of self-sustaining decomposition meaning that cargoes which were tested and certified as “ammonium nitrate fertiliser (non-hazardous)” could give rise to serious incidents.

I have, over the years, been consulted many times regarding proper classification of materials containing ammonium nitrate. I suspect the new provisions, whilst being technically more complete and consistent than the previous version, will also result in queries. That is because they are even more complicated.

In the new Code, 2022 edition, we now have (in the order they appear in the Code)

AMMONIUM NITRATE UN1942. This schedule is unchanged from previous versions which covers ammonium nitrate itself. It is a Group B schedule, Class 5.1 oxidiser and is an extremely hazardous substance. The schedule sets very strict limits on the amounts of combustible material.

AMMONIUM NITRATE BASED FERTILISER UN2067. This is also Group B, Class 5.1 and is carried over from previous versions. There are compositional limits set for this category of fertiliser derived from ammonium nitrate which result in it being less hazardous than the UN1942 material.

AMMONIUM NITRATE BASED FERTILISER UN2071. This is also carried over from previous Code versions and is a Class 9 Group B material. This schedule applies to ammonium nitrate based fertilisers with compositional limits set to result in material less hazardous again than UN2067 or 1942. The substance is no longer sufficiently oxidising to result in a Class 5.1 designation but is Class 9 because it can undergo self-sustaining decomposition. This and the remaining two schedules are where the new provisions start to become somewhat complicated to follow. A fertiliser which passes the UN Trough Test is not subject to the provisions of this schedule.

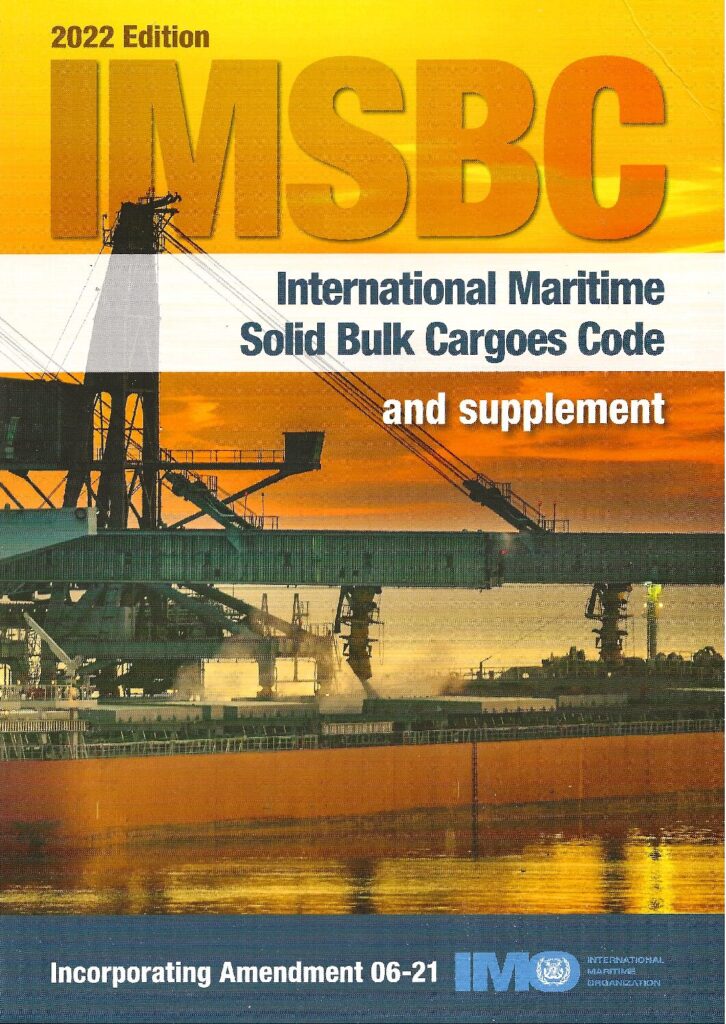

AMMONIUM NITRATE BASED FERTILISER. Note that the designation “non-hazardous” is no longer present. This is a Group C schedule which, together with the MHB schedule below replace the old “non-hazardous” schedule. The Group C schedule says it applies to mixtures which fall within certain limits defined by the amount of ammonium nitrate and the amount of chloride present. To be within the Group C schedule, the material has to fall within the grey shaded area in the graph reproduced below. Note that either the amount of ammonium nitrate is very low or the amount of chloride is very low (or both).

There is a provision in this schedule that materials which fail the trough test are excluded from the schedule. It is a stated hazard that Group C ammonium nitrate based fertiliser will decompose if exposed to heat, but that decomposition is “highly unlikely” to spread through the bulk.

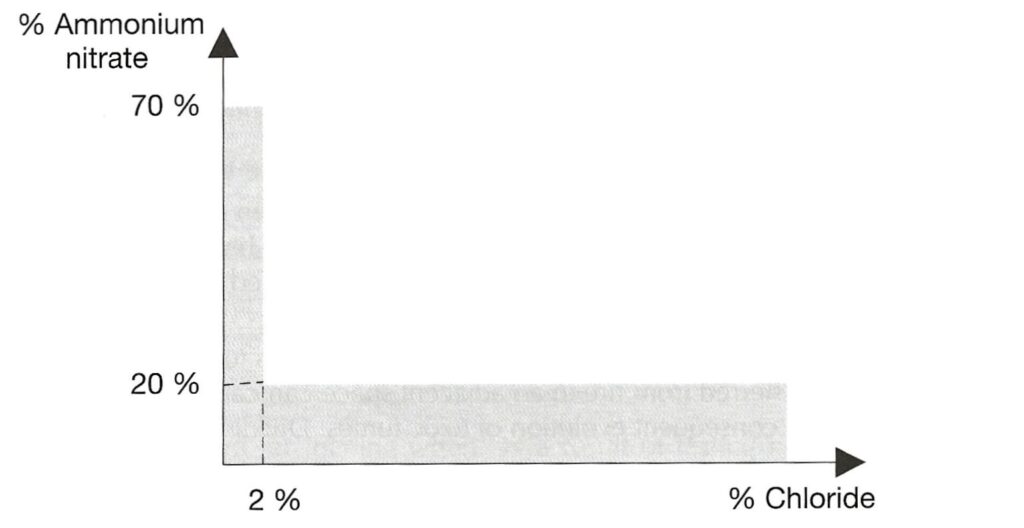

AMMONIUM NITRATE BASED FERTILISER MHB is the final schedule, and this is wholly new. It is categorised as Group B, hazardous only in bulk (MHB) of type “OH” (other hazard). This means a hazard which is not one of the standardised ones. The schedule includes a definition in terms of compositional basis to distinguish it from the Group C material above. The graph is the complement of the one reproduced above – i.e. it covers material with more ammonium nitrate or more chloride or both but not sufficient ammonium nitrate to make the material one of the more hazardous types.

Again, the schedule states that material which fails the trough test is excluded. This MHB schedule only applies to substances which pass the trough test. However, this schedule states that this material has the hazard that an initiated decomposition event can propagate through the bulk.

This new schedule then accommodates ammonium nitrate fertilisers which pass the trough test but do actually possess the hazard the trough test was designed to detect. The schedules appear to have been written in this manner as a work-around for the fact that the trough test does not detect all fertiliser mixtures which can undergo self-sustaining decomposition.

I note that historically, research has shown that self-sustaining decomposition is only a possibility with a mixture which includes ammonium nitrate and chloride (generally NPK fertilisers where the K element is supplied by potassium chloride/muriate of potash). That is the basis behind the graphical composition criteria.

Working backwards, the effect of the new provisions is as follows. Firstly, materials which are compositionally UN1942 or UN2067 remain covered by those schedules. Any other fertiliser material which contains ammonium nitrate and fails the trough test is Class 9 UN2071.

The remaining two schedules apply to any substances which pass the trough test, and which one applies depends on the levels of ammonium nitrate and chloride. The implication of the criteria is that ammonium nitrate fertiliser with below 20% ammonium nitrate or below 2% chloride can be assumed not likely to undergo self-sustaining decomposition and can be consdered Group C. The MHB schedule covers the rest, and presumably would have applied to the CHESHIRE cargo and the PURPLE BEACH cargo had the new schedules been in existence at the time those cargoes were shipped. [Note that I am not party to technical data regarding the cargoes on these two vessels but assume this to be the case.]

How does this new set of schedules benefit the seafarer? Well, the MHB schedule is the one to focus on because it encompasses substances which were prevoiusly categorised as non-hazardous despite being capable of leading to the total loss of a vessel such as CHESHIRE. The big difference is that the seafarers will be aware of the potential risk and will therefore be more likely to detect it early if it happens. The Code outlines a number of precautions to be taken when MHB ammonium nitrate based fertiliser is carried, and some provisions indicating what to do if a decomposition event is detected during the voyage.

Hopefully the new schedules will assist in avoiding these horrific events.

A new Code – Part 1

It has been a while since I wrote here. Things have been madcap busy at Sheard Scientific. There’s just enough time now after digesting another turkey lunch for me to digest the contents of a new edition of the IMSBC Code, which landed on our doormat here at Sheard Scientific this month. I will start with this article by outlining what is in the Code and how it all works. Tomorrow, I will set out what has changed.

This tips the scales at a hefty 2.2kg. Quite a weighty document – the bulky code perhaps!

There is of course a reason for this. When the old BC Code morphed into the first version of the IMSBC Code and became mandatory under SOLAS, it contained schedules for individual bulk cargoes and a mechanism for missing or incorrect schedules to be identified and added. Those processes have been in place now for a number of years, and on each new edition, the Code gets bigger and bigger, and heavier.

The concept was that any cargo carried in bulk (other than grain cargoes, and many don’t properly understad why they are not covered) will have its own schedule. In that schedule will be a listing of the properties and hazards of the material and guidance regarding carriage.

The amendment timetable has been disturbed a little by Covid. The new edition is now available in print, and can be applied on a voluntary basis from 1st January 2023 and becomes fully mandatory on 1st December. This pattern – of publication followed by a period of voluntary applicability and then full force has been the case for previous amendments.

It is important to note that the concept of “voluntary” applicability is voluntary in the sense that the relevant Competent Authority/participating governmental body to IMO can decide that the new Code applies. It is not left to be a voluntary decision by individual shipowners, ship Masters, or indeed cargo shippers.

As the amendments to a document such as the IMSBC Code by definition represent best practice in the industry, it should in my view be in everyone’s interest for the amendments to be adopted as soon as practicable.

It is worth taking a quick look through the material making up the Code as published. Some things are in surprising places – this is to an extent a legacy of a shake-up of organisation as the material which used to be in various locations in the BC Code is mostly still to be found, just not necessarily where you might think it would be.

Sections 1-13 are where procedures, rules and regulations, and definitions are to be found. Material specifically relevant to liquefaction for instance can be found in sections 4, 7, 8, but you might also need to check section 5, which relates to trimming. There really is no substitute to reading through these sections carefully even if just to know what can be found where.

The next part of the Code is the appendices. Unlike most books, the appendices to the IMSBC Code are a fundametal part of the contents. Appendix 1 on its own is nearly 400 pages long, and contains the individual schedules for bulk cargoes, listed alphabetically by Bulk Cargo Shipping Name. These schedules are the part of the Code which a vessel’s Master will spend most time looking through, and this is the part of the Code which enlarges on each amendment as additional schedules are added.

Appendix 2 contains test methods applicable to bulk cargoes. This includes all six tests for Transportable Moisture Limit along with other tests.

Appendix 3 is headed “Properties of solid bulk cargoes” and is a curious mixture of seemingly unconnected but very important sections. One important point to bear in mind is that the contents of this appendix are not legally mandatory under SOLAS whereas some other parts of the Code are.

- Appendix 3 point 1 is a list of non-cohesive cargoes (as contrasted with other cargoes which are considered cohesive) and some provisions which flow out of this property.

- Appendix 3 point 2 is a single paragraph which describes the types of cargoes which might undergo liquefaction or dynamic separation. This paragraph is often quoted in disputes, so I will quote it here.

Many fine-particled cargoes, if possessing a sufficiently high moisture content, are liable to flow. Thus any damp or wet cargo containing a proportion of fine particles should be tested for flow characteristics prior to loading.

IMSBC Code Appendix 3 paragraph 2.1

- Appendix 3 point 3 is a provision which states that where a Competent Authority has to be consulted prior to shipment (i.e. substances not listed in the Code or substances with hazards which differ from that listed in the Code), the corresponding authorities at the loading and discharge port should be consulted. This is to ensure that all potentially involved in the carriage of a substance with chemical hazards are aware and agree with the precautions being taken.

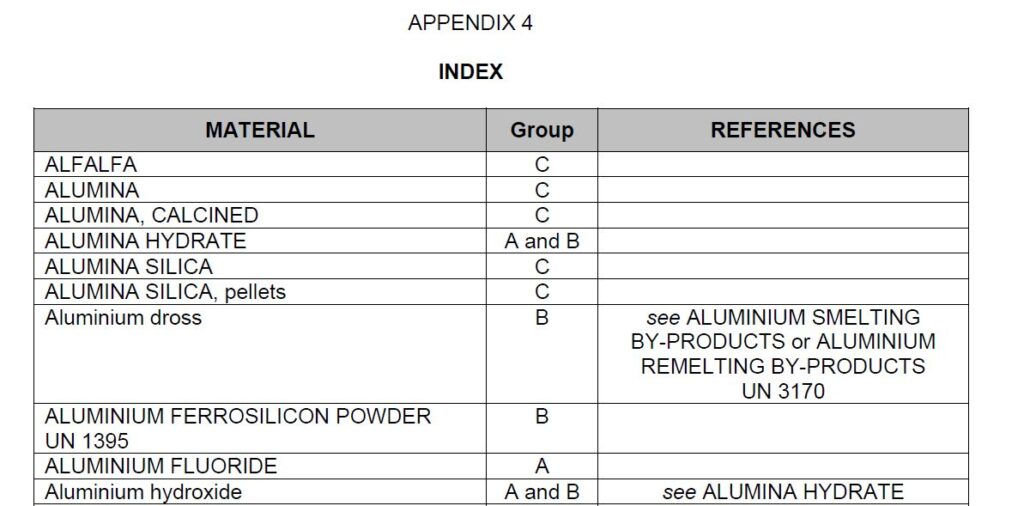

Appendix 4 is the Index. However, it is much more than just an index. As stated above, the list of schedules in Appendix 1 is arranged alphabetically and so acts as its own index to an extent. In Appendix 4, the Index also includes entries which cross-reference to a BCSN. These can be found in lower case entries in the Index whereas entries in capital letters are the BCSNs themselves. As an illustration of how this works, the fourth entry in the Index is ALUMINA HYDRATE, a Group A&B cargo. The capital letters denote that ALUMINA HYDRATE has a schedule under that name in Appendix 1. Lower down on the same page can be found Aluminium hydroxide. As this is in lower case, it isn’t a BCSN and there is no schedule in Appendix 1 for Aluminium hydroxide. However, the entry says “see ALUMINA HYDRATE” and so the reader is thus informed that aluminium hydroxide and alumina hydrate are synonymous from the viewpoint of the entries in the Code. There are many other examples of this type of cross-referencing in the index.

Appendix 5 is similar to an Index but contains BCSNs from the Code in English, French and Spanish.

The rest of the book as published is the Supplement to the Code, and this amounts to a further 150 pages.

The documents making up the Supplement are all also published separately in their own right or as IMO circulars. They cover a wide range of topics, starting with the BLU Code (Code of Practice for the Safe Loading and Unloading of Bulk Cargoes) and ending with an alphabetic list by country of the designated Competent Authorities.

More or less in the middle of the Supplement can be found the document “Recommendations on the safe use of pesticides in ships applicable to the fumigation of cargo holds” which is also published as IMO Circular 1264. This is a vitally important set of guidelines and recommendations which is essential reading for any becoming involved with shipboard fumigation, whether that is carried out in port or when continued in transit. I mentioned this circular earlier this year in the context of a serious incident involving fumigation.

Season’s Greetings

Sheard Scientific would like to wish all of our friends and valued clients a very happy Christmas and a prosperous New Year.