It has recently been in the news in shipping circles that permission has not been granted for the TAI PRIZE dispute to be taken to the Supreme Court, and so the Court of Appeal judgement is the final word on the matter.

I wasn’t involved in the TAI PRIZE and I am not aware of the finer details of the case and what facts the arbitrator and judges had at their disposal. So, I’m not going to write about the TAI PRIZE, or the legal issues it deals with, but I am going to talk about soya beans and “apparent good order and condition”.

I have been inspecting cargoes of soya beans for more years than I’d like to say. It seems to be a commodity which causes a great deal of trouble worldwide. In recent years, the focus of many claims has been the trade from Brazil to China, but there have been plenty of cases involving soya beans of different origin and in different discharge ports.

As with agricultural materials generally, there is a tendency for soya beans to deteriorate microbiologically when overmoist. Unlike many other commodities, soya beans have a relatively large oil content. When vegetable oils oxidise, the chemical reaction releases heat. That means that soya beans can self-heat to rather higher temperatures than maize or rice. At elevated temperatures, further chemical reactions between proteins and sugars which result in the beans discolouring through a variety of shades of beige to brown and eventually black. These are known as Maillard reactions (nothing to do with ducks!) and they are also the reactions which take place when food is cooked.

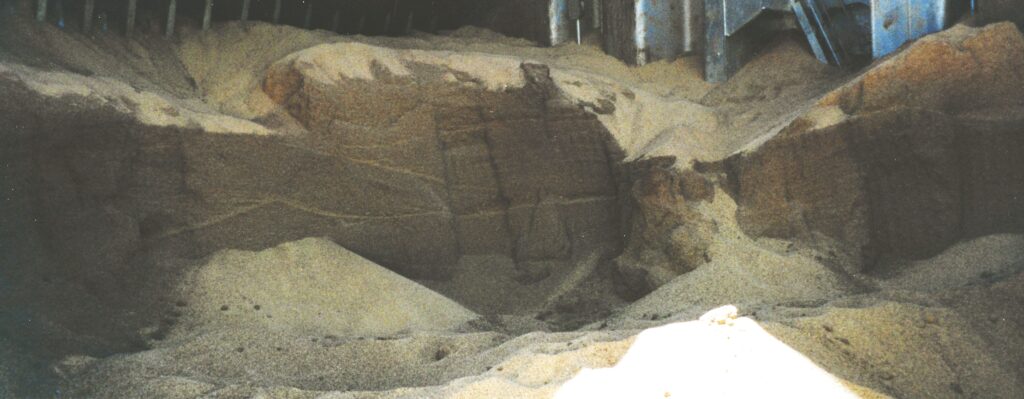

People doing my sort of work tend to give presentations exhibiting lots of dramatic photographs like the above. They make good slides in powerpoint presentations! But these are photographs of holds in which there has been a major problem with soya beans. They aren’t representative of normal shipments.

Incidentally, the phrase “burned” is often bandied about to describe beans which are heavily darkened or even blackened. To actually set soya beans on fire requires quite a bit of effort, but it can be done. They then will burn, slowly. Heavily darkened beans where the darkness has arisen by means of elevated temperatures created by self-heating, and the Maillard reactions which result, are not burned.

And so to the “apparent good order and condition” point. This term has a legal meaning which hangs on the word “apparent” – it relates to what can be seen by normal inspections by a ship’s Master and the crew during loading.

The most recent grain case I have handled had just under 45000MT of grain loaded in 49 hours. That is on average just over 900MT an hour. A single soya bean weighs about 0.15g. So in each hour, some 6×109 beans are loaded. In American terms that is six billion; in British terms six thousand million beans.

Add to that the fact that the crew member in question might be standing by the hatch looking in. The nearest cargo is several metres away. There will be a cloud of dust hanging over the hold for much of the time, and there won’t be much chance of seeing through that cloud to notice anything much about the beans.

The first thing which definitely does not come under “apparent good order” is moisture content. This is a hugely important parameter as it plays a significant role in determining whether cargo will carry without deterioration. It isn’t a visible one, except in very extreme cases.

Soya beans which appear visibly wet would have to have a moisture content in excess of 30-40% and would be visibly saturated. However, the difference in moisture levels which give rise to problems in soya bean cargoes on ships are differences between 12%, 13%, 14% and so on. These all look identical. Very often I hear mouldy or otherwise damaged grain and soya bean cargoes referred to as being “wet”. They usually are not actually wet.

So, except in extreme cases, you can’t see problematic moisture contents. Sometimes we see recommendations for having a surveyor present to take small samples and measure moisture levels. There are portable moisture meters which can be used to get a rapid result on a ship. Obtaining a sample and using the meter might take 5 minutes if the surveyor is efficient. In that time in the example above some 75MT of cargo (500 million beans) may have been loaded. As the moisture content doesn’t have any impact on “apparent good order and condition”, what do you then do with that information? If the figures are such that an expert would tell you there is a strong chance of deterioration on a given voyage, what then do you do?

The next thing which isn’t “apparent good order” is the cargo temperature. You cannot see it. Is it a good idea for temperatures to be taken during loading? Wholeheartedly yes. There are lots of reasons why knowing the cargo temperature at loading can be useful. Soya beans which are significantly warmer than ambient temperature may represent parts of a cargo which have already started to deteriorate before shipment. That is certainly something you would want to know about, and it is likely that such cargo would also have elevated levels of mouldy or discoloured beans, and in all likelihood, an unpleasant odour.

Choosing the right thermometer for a given situation is quite important. Spear probes may be necessary for some situations and these can take time to use properly. For taking rapid and plentiful readings during loading of a cargo of soya beans, an inexpensive infra-red remote thermometer gun is ideal. These only report the temperature of the nearest surface in front of the gun, but that’s fine for such situations. Accuracy down to a fraction of a degree isn’t important but a real-time indication of whether warm cargo is being loaded can be.

The next biggie which is not part of “apparent good order” is cargo quality. With soya beans, there are a number of parameters. Foreign material (you can see seed pods and other foreign material in the photograph above) is one. Dust and other foreign material is often airborne during loading and it settles into a layer on top of the cargo during a break in loading. Those layers can often be seen in and amongst the cargo when it has heated – see the top photograph earlier in this article. Sales contracts have allowances for foreign material, and also other parameters such as split beans, heat damaged beans, and so on. To measure the levels of these it is necessary to take representative samples and have them analysed. This is well beyond the scope of what would be considered part of the duties of the crew during a loading, and quality matters are not relevant considerations for “apparent good order and condition”, even though the individual items of foreign material and the split beans etc are visible to the unaided eye.

So, having discussed a few categories of issue which are not “apparent good order and condition” items, and having said that quality parameters are not, what about a part of the cargo where the beans are discoloured, or mouldy, etc? This is where it gets more complicated. An example of an assembly consisting exclusively of darkened beans, or where such beans are in a majority, is in the top photograph above and the two below.

These photographs were taken during a cargo discharge, but if a significant quantity of such beans was loaded into one part of a ship’s hold, and then that inspected, it may well be considered not to be in “apparent good order and condition”. That is because a parcel of discoloured beans does not look like a normal parcel of soya beans.

What’s the likelihood of something like that being spotted? Answering that is much more difficult. The rapid rates of loading typical at grain terminals and the dust generated make it very difficult for even gross problems such as these to be detected. It would be very easy for even a large parcel of discoloured beans to be loaded and covered with other cargo without even the most attentive crew member noticing the problem.

Experts analysing evidence from a discharge may make the judgement that the cargo deteriorated because of its inherent condition (so-called inherent vice). Deciding that a certain parcel of cargo was already damaged at the time of loading is very much harder to do. Sometimes the evidence does suggest this. It is very much more difficult again to determine whether that could or should have been detected at loading.